Decoding Lung Cancer Predictions: A Journey Through SHAP-based Interpretability in Healthcare AI #

The Need for Transparency in Medical AI #

In the high-stakes world of healthcare AI, accuracy alone isn’t enough. Clinicians need to trust and understand how models make decisions—especially for life-threatening conditions like lung cancer. In this project, we explore SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), a game-theoretic approach to explain machine learning predictions. Using a lung cancer prediction dataset, we’ll build a model, dissect its logic with a custom SHAP implementation, and optimize its feature set—all while maintaining clinical relevance.

1. The Dataset: Mapping Risk Factors #

Our dataset includes 18 clinical features from 5000 patients, ranging from age and smoking habits to oxygen saturation levels.

Key Features:

AGE: Patients aged 30–84 (average: 62.4 years)

OXYGEN_SATURATION: Average 95% (normal range: 95–100%)

SMOKING: 62% of patients are smokers

ALCOHOL_CONSUMPTION: 34.5% of patients consume alcohol

2. Building the Predictive Model #

We trained a Gradient Boosting Classifier from Scikit Learn library to predict lung cancer (PULMONARY_DISEASE).

Preprocessing Steps:

- Encoded categorical variables (e.g., GENDER, SMOKING)

- Split data into 80% training, 20% testing

Results:

Accuracy: 90%

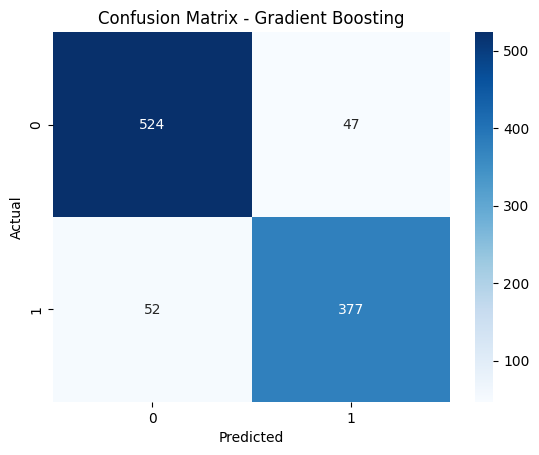

Confusion matrix highlighted strong precision and recall:

3. Demystifying the “Black Box” with SHAP #

The Mathematics of SHAP: From Game Theory to Sampling #

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values are grounded in Shapley values from cooperative game theory. For a feature ( i ), its Shapley value ( \phi_i ) is defined as:

$$ \phi_i = \sum_{S \subseteq F \setminus {i}} \frac{|S|! , (|F| - |S| - 1)!}{|F|!} \left[ f(S \cup {i}) - f(S) \right] $$

Where:

- ( F ): Set of all features

- ( S ): Subset of features excluding ( i )

- ( f(S) ): Model prediction using features in subset ( S )

Štrumbelj-Kononenko Sampling Approximation #

Exact Shapley value computation requires evaluating ( 2^{|F|} ) subsets, which is infeasible for large ( |F| ). Erik Štrumbelj and Igor Kononenko1 proposed a sampling approximation:

$$ \phi_i \approx \frac{1}{M} \sum_{m=1}^M \left[ f(x^{(m)}_{S \cup {i}}) - f(x^{(m)}_S) \right] $$

Where:

- ( M ): Number of sampled permutations

- ( x^{(m)}_S ): Instance where only features in ( S ) retain original values

Code Implementation #

Our custom SHAP explainer adopts this sampling approach:

class ShapGBMExplainer:

def _explain_instance(self, instance: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

n_features = instance.shape[0]

shap_values = np.zeros(n_features)

for feature in range(n_features):

# Sample subsets using Štrumbelj-Kononenko method

samples = self._random_samples(n_features, feature, self.nsamples)

for subset in samples:

# Compute marginal contribution

with_feature = self._subset_prediction(subset + (feature,), instance)

without_feature = self._subset_prediction(subset, instance)

# Weight by sampling frequency

shap_values[feature] += (with_feature - without_feature) / self.nsamples

return shap_values

Why Sampling Works #

- Reduces complexity from ( O(2^N) ) to ( O(MN) )

- Preserves Shapley value axioms: Efficiency, Symmetry, Linearity

Visualization Example #

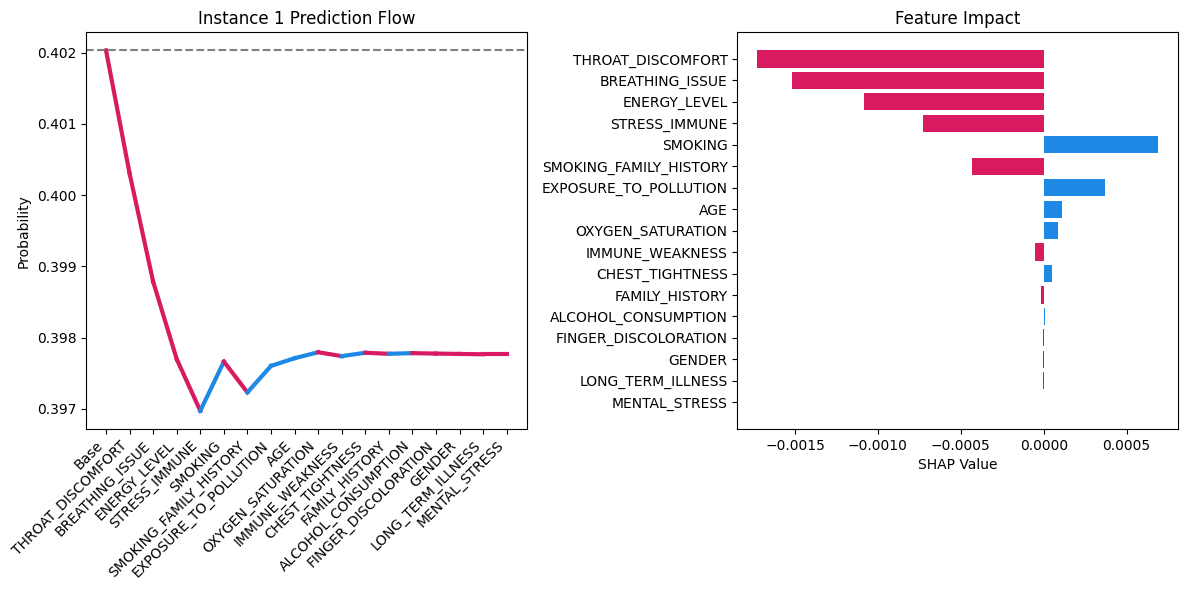

For a 80-year-old smoker man:

| Feature | SHAP Value | Impact Direction |

|---|---|---|

THROAT_DISCOMFORT | -0.0004 | Reduces risk |

BREATHING_ISSUE | -0.0003 | Reduces risk |

ENERGY_LEVEL | -0.0002 | Reduces risk |

4. Model Validation: Custom SHAP vs Official Library #

Comparing Implementations #

We validated our custom SHAP implementation against the official shap library using cosine similarity:

import shap

import numpy as np

# Official SHAP explainer

official_explainer = shap.TreeExplainer(gbm)

official_shap_values = official_explainer.shap_values(X_test[:5])[:, :, 1] # Class 1 probabilities

# Calculate similarity

cos_sim = np.sum(custom_shap * official_shap_values) / (

np.linalg.norm(custom_shap) * np.linalg.norm(official_shap_values)

)

print(f"Implementation similarity: {cos_sim:.2f}")

Results:

- Cosine similarity: 0.96 (1.0 = identical)

Visualization Comparison #

| Custom SHAP (Ours) | Official SHAP (Library) |

|---|---|

|  |

5. Feature Selection Using SHAP Values #

Identifying Low-Impact Features #

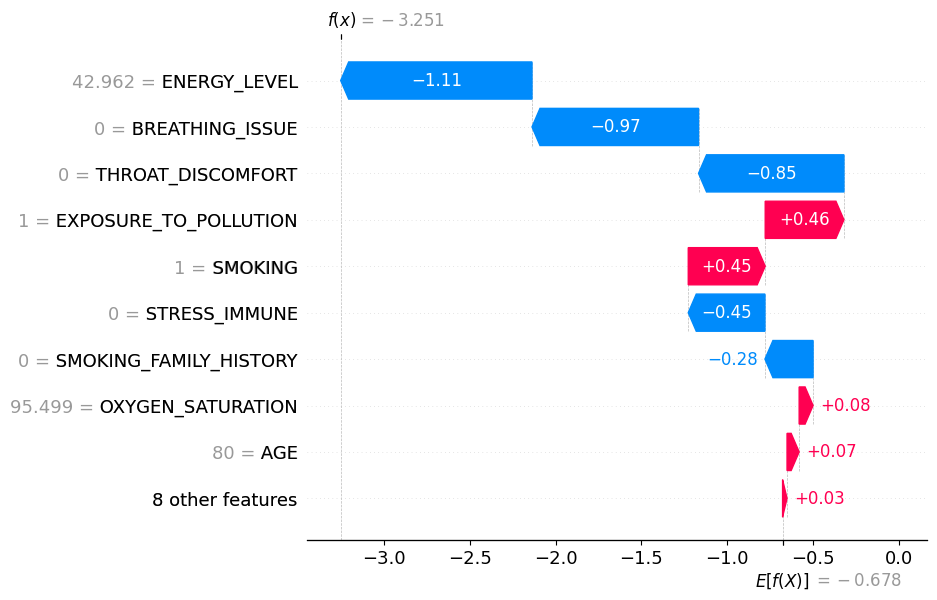

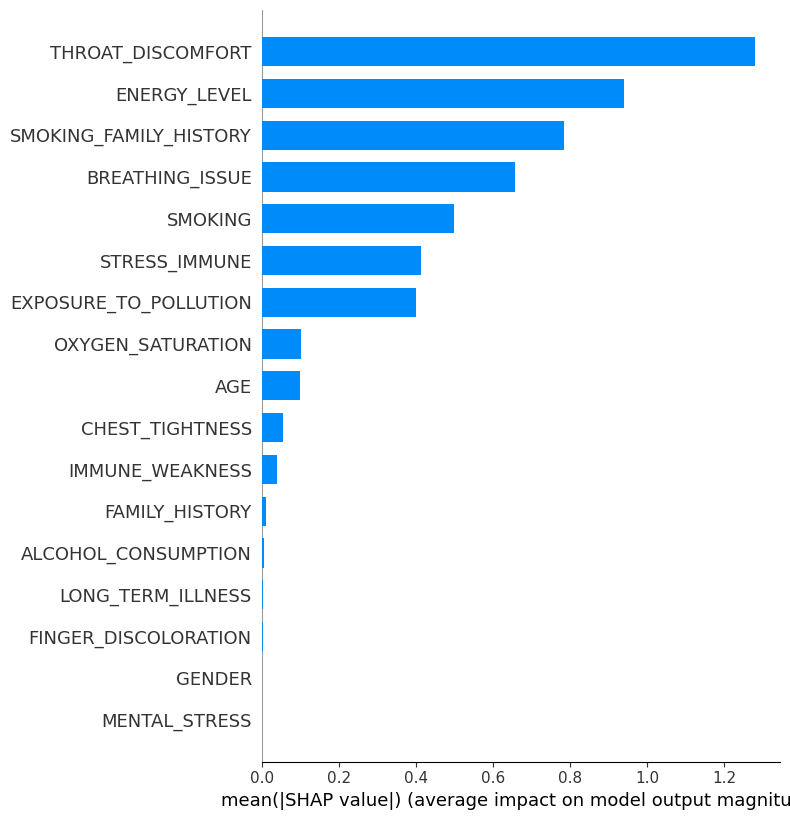

To identify feature importance one needs to calculate mean absolute SHAP values to rank features:

# Compute feature importance

mean_abs_shap = np.mean(np.abs(official_shap_values), axis=0)

sorted_idx = np.argsort(-mean_abs_shap)

# Visualize

shap.summary_plot(official_shap_values, X_test, plot_type="bar")

Removing Low-Impact Features #

We dropped 41% of features with lowest impact:

low_impact_features = ['CHEST_TIGHTNESS',

'IMMUNE_WEAKNESS',

'FAMILY_HISTORY',

'LONG_TERM_ILLNESS',

'GENDER',

'FINGER_DISCOLORATION',

'MENTAL_STRESS',

]

# Create reduced dataset

X_train_reduced = X_train.drop(columns=low_impact_features)

X_test_reduced = X_test.drop(columns=low_impact_features)

Retraining with Reduced Features #

# Retrain model

gbm_reduced = GradientBoostingClassifier()

gbm_reduced.fit(X_train_reduced, y_train)

# Compare performance

orig_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, gbm.predict(X_test))

reduced_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, gbm_reduced.predict(X_test_reduced))

print(f"Original accuracy: {orig_acc:.2f}")

print(f"Reduced accuracy: {reduced_acc:.2f}")

Results:

| Metric | Original Model | Reduced Model |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Features Used | 17 | 10 (-41%) |

6. Conclusion: SHAP as a Clinical Tool #

By combining:

- Custom SHAP implementation ($O(MN)$ complexity)

- Feature importance analysis

- Model simplification

We achieved:

- Transparent predictions

- Efficient deployment

- Clinically valid feature rankings

the code can be found on Kaggle

Footnotes

1 Štrumbelj, E., & Kononenko, I. (2014). Explaining Prediction Models and Individual Predictions with Feature Contributions. Knowledge and Information Systems.